The undeniable existence of the apparently invisible, the dignity of the seemingly

insignificant, and

the quest for an esthetic to render their testimonies were at the heart of Nacho López’s

photography for

illustrated magazines during the 1950s.

Digital resource

He constructed his own definition of "lo mexicano" by documenting the plurality of many

Mexicos

in his photoessays about “worlds apart”. The poor, the prisoners, and the Amerindians who peopled

some

of his finer photoessays were distant from the middle-class readers of the illustrated magazines.

And,

they also came from other universes than the homogenous vision offered by the party dictatorship of

the

pri (Partido Revolucionario Institucional): presidential

preeminence,

the monopoly of power, the skilled manipulation of mass organizations, and the dilution of class

difference and ideology in the dissolvent of nationalism.

He explained his critical position by referring to his early education, “The socialist education I

received as an adolescent during the reign of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940) left a profound imprint on

my

soul.” Fusing social commitment with formal exploration makes him part of a very select company of

great

photographers, including Tina Modotti, Paul Strand, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Paolo Gasparini,

Sebastião Salgado, and the photographer who most he admired and resembles, W. Eugene Smith. And it

is

precisely that dialectic that made Nacho the extraordinary imagemaker he was.

His photoessays were published in the most important Mexican illustrated magazines, among them,

Hoy, Mañana, y Siempre! (Today, Tomorrow, Always!). He always worked for

weeklies,

never in newspapers, and almost never covered hard news. In fact, I do not believe that his metier

was

spontaneous or street photography, but the magazine genre of “features” made up of human interest

stories. However, photojournalism is a very wide field, and the capacities of photographers should

be

understood to be as varied as those who write. In spite of the general perception of him as a

photoreporter, I think he would be better described as a photoessayist in the majority of his

publications.

John Mraz

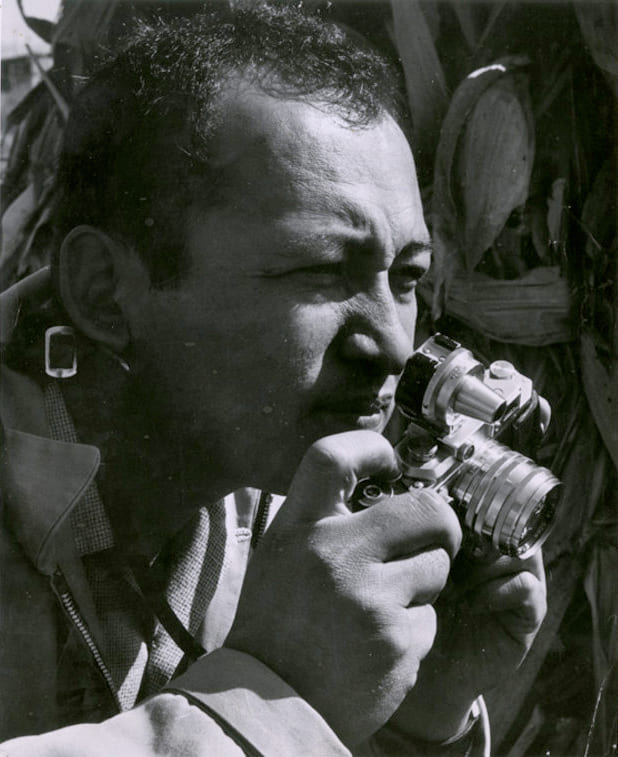

The hundredth anniversary of his birth provides opportunity to remember the artist, his images, his

ideals, everything that shaped one of the most important photographers of 20th century Mexico. Ignacio

López Bocanegra (Tampico, November 20, 1923 - Mexico City, October 24, 1986), better known as Nacho

López, was driving force of photography who pushed far beyond conventional, established, and authorized

limits. A man of lofty ideas and left-wing convictions, he showed us a very different path for

approaching photography. His camera recreated photojournalism, photoreportage, and above all, innovated

with photo essays—, an avant-garde journalistic genre —alongside editors José Pagés Llergo and Regino

Hernández Llergo. With the coming of Nacho López, photographers became professionals, independent

creators with their own visual grammar, catapulting the profession to another level within the editorial

and journalistic world.

It is important to note that Nacho López revealed an unusual Mexico in his work; that of the

underworlds, a Mexico that slumbered while life continued on the surface, that of the helpless or

dispossessed. Concurrently, he also worked with other subjects such as dance, music, the city,

architecture, the countryside, indigenous people in their native land, objects, and a vast array of

unusual themes for photography at that time. The genre overflowed with the everyday, treated with a

sharp sense of humour, accentuating social and political contradictions. In addition to an aesthetic he

developed, his images would penetrate diverse worlds, he was a great teacher and example with his

camera, always at the ready. It was part of his way of conversing, contrasting, discussing; he taught

his students a sharp-witty and fierce visual discourse. López was one of the few photo creators who used

printed words to show us the paths of visual militancy and the need to construct a discourse that would

surpass the known. He revealed, taught, and exercised that historical visual consciousness and from it

we learned how to comprehend the importance of photography as a documentary, historical, social, and

aesthetic source. Furthermore, his interest led him to cinematography with the same zeal.

In the case of this exhibition, it is an honour to share the words and curation of researcher and photo

historian John Mraz—the most prominent specialist in the work of Nacho López, who presents the

photographer on the hundredth anniversary of his birth through the full force and quality of his images.

Thanks to John Mraz, new generations will be able to familiarize themselves with one of the best

photographers in Mexico.

Rebeca Monroy Nasr

deh-inah

John Mraz

John Mraz

Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades

Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla

John Mraz is Research Professor Emeritus at the icsyh-buap and National Researcher Emeritus. He has

published more than 250 articles, book chapters, and essays in Europe, Latin America, and the United

States on the uses of modern media in recounting history. Among his recent books are History and

Modern Media: A Personal Journey; Photographing the Mexican Revolution: Commitments,

Testimonies,

Icons; Looking for Mexico: Modern Visual Culture and National Identity; and Nacho

López, Mexican

Photographer. He has directed award-winning documentaries, and curated many international

photographic exhibits. His most recent documentary, Julio Mayo: Bracero with a Camera, and

exhibit,

Braceros, Photographed by the Hermanos Mayo, is currently circulating in U.S. universities and has

been viewed by more than 140,000 visitors.

Mraz, John, Nacho López y el fotoperiodismo mexicano en los años cincuenta, México, Editorial

Océano / inah, 1999.

_________, Nacho López, Mexican Photographer, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press,

2003.

Nacho López, fotógrafo de México, Homenaje, México, inba /

Museo de

Bellas Artes, 2016.

Revista Luna Córnea,

núm. 31, Secretaría de Cultura, Centro de la Imagen, 2007.

Rodríguez, José Antonio y Alberto Tovalín Ahumada (eds.), Nacho López, ideas y visualidad,

México, inah / sinafo /

Universidad Veracruzana / Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2012.