Disputes over the use of streets and over the transportation business shaped the transition in urban mobilities. In the 1920s, the city was a complex space where pedestrians could pass by horse-drawn carts, electric trams, and motor vehicles. Agustín Lazo noticed tensions inherent to this moment of transition. His 1924 watercolor not only portrayed a traffic accident but the collision between different forms of understanding a city and the consequences in the lives of its residents. By the middle of the century, it was clear that cars and spaces exclusive to them ruled mobility in Mexico City.

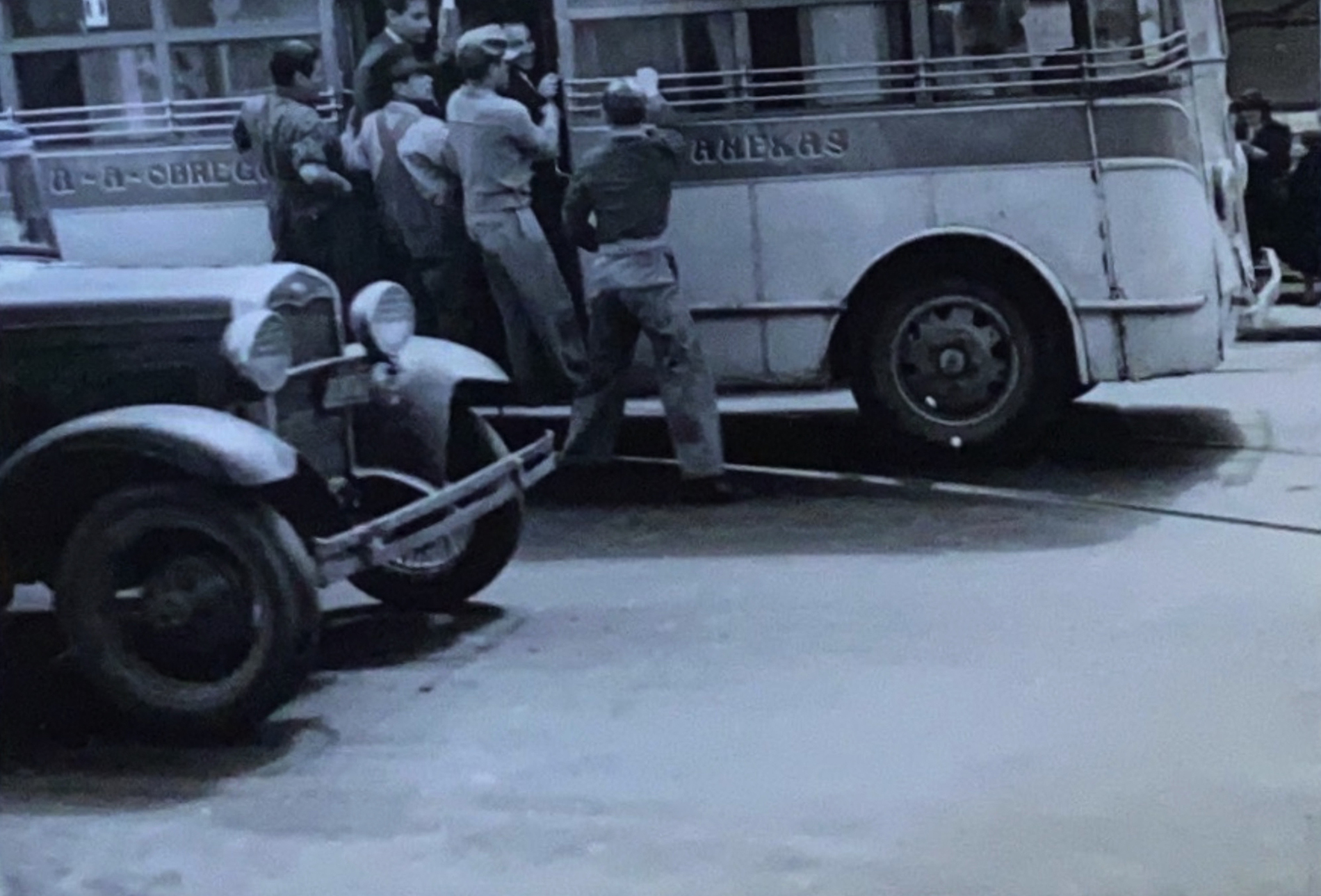

At the beginning of the twentieth century, no one could predict the future predominance of cars. Streets were the daily stage of competition between tramway workers, the Mexican Tramways Company, and chafiretes. During a massive strike by tramway workers in 1925, a cartoon in El Universal outlined the tensions of this process: chafiretes fought for passengers, but buses did not have the capacity to provide the service for a growing.

Mexico Tramways Company officers feared competition by chafiretes in the mid-1920s. In public, they highlighted the advantages of trams over buses: “... electric trams can transport real crowds on their own and [...] will never be replaced by buses.” Behind closed doors, however, correspondence between executives in Mexico City, Toronto, and London conveyed the “considerable anxiety” they felt about the “dangerous and disorganized competition” by bus drivers.

To win the favor of public opinion, the company spread propaganda linking trams with a sense of collective mobility that, by association, was democratic. In contrast, the car was a private vehicle for a privileged few.

The Mexico Tramways Company appealed to social distinction. As their propaganda said: “Classy people travel by tram.”

However, the quality of the streetcar service declined from the 1920s onwards. Crowding, commuting times, and the lack of tram routes in some areas became issues impacting the daily lives of city residents. Were there any alternatives?

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, the automobile was presented as a cure for social, economic, and political issues. During the Mexican Revolution, Henry Ford suggested bringing peace and modernity to the country through employment in industrial complexes for the mass production of automobiles that would interconnect towns:

“In Mexico villages fight one another. If we could give every man in those villages an automobile, let him travel from his home town to the other town, and permit him to find out that his neighbors at heart were his friends, rather than his enemies, Mexico would be pacified for all time.”

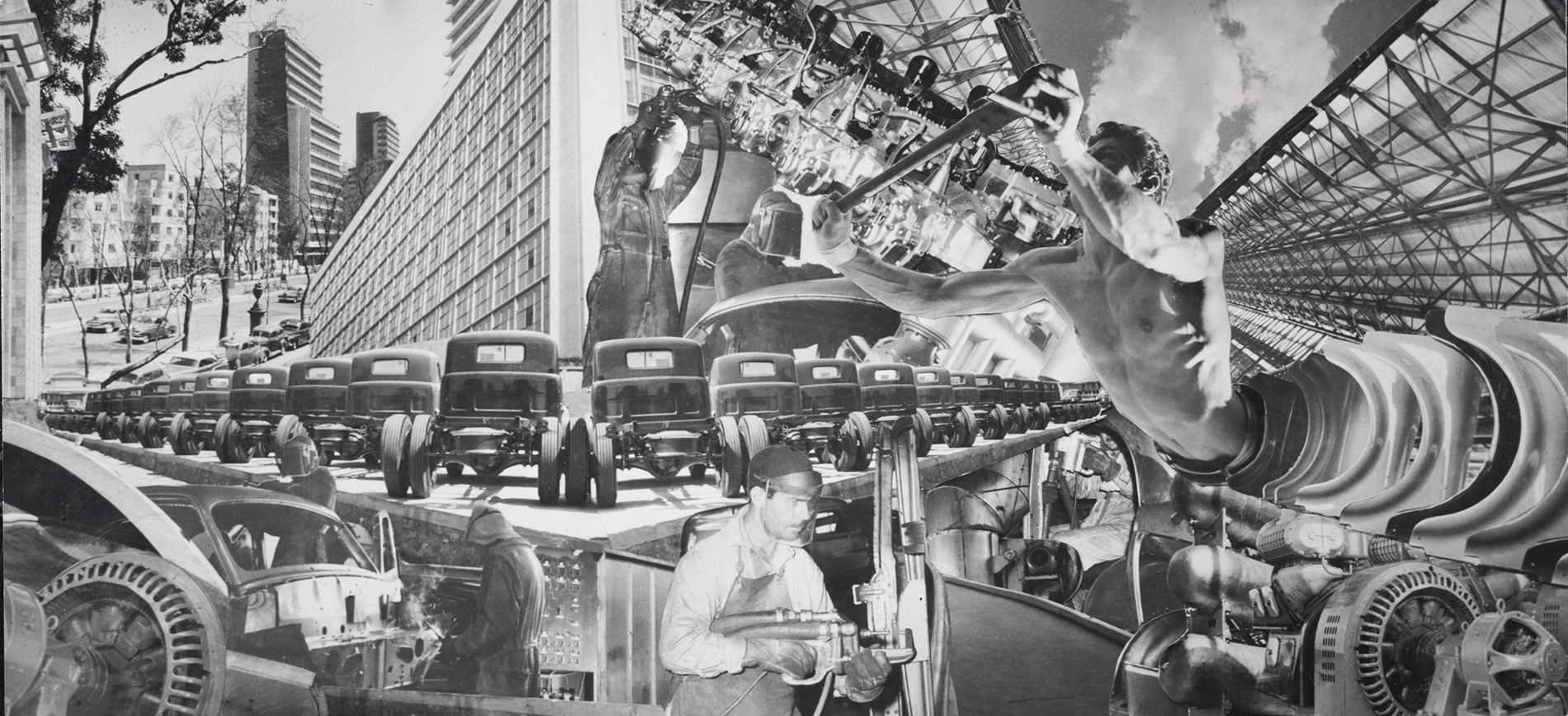

Ford Motor Company incorporated into the international chain of mass production in the following decades. In 1925, Ford Mexico opened its first assembly plant in the city. Two decades later, photographer Lola Álvarez Bravo captured the principles of Fordism —work efficiency, product standardization, and mass production— as an experience that linked labor, transportation, and the city.

What advantages did cars offer over trams in Mexico City during the 1920s and 1930s?

-

Trams needed tracks following a fixed route. These were centralized from downtown Mexico City outwards. In contrast, chafiretes drove their buses and cars on any drivable road.

-

The tram service simply could not reach some places. From the 1920s, neighborhoods were built along roads or designed to be inhabited by car drivers and bus passengers.

However, the advantage of buses and cars over trams was not simply technological, but also a matter of power, interests, and decision-making. Like Ford, politicians, businessmen, urban planners, and city dwellers saw in cars practical solutions to urban problems, means for modernization, and business opportunities. Their decisions rearranged urban space so that private cars and buses could circulate. In consequence, internal combustion vehicles multiplied exponentially.

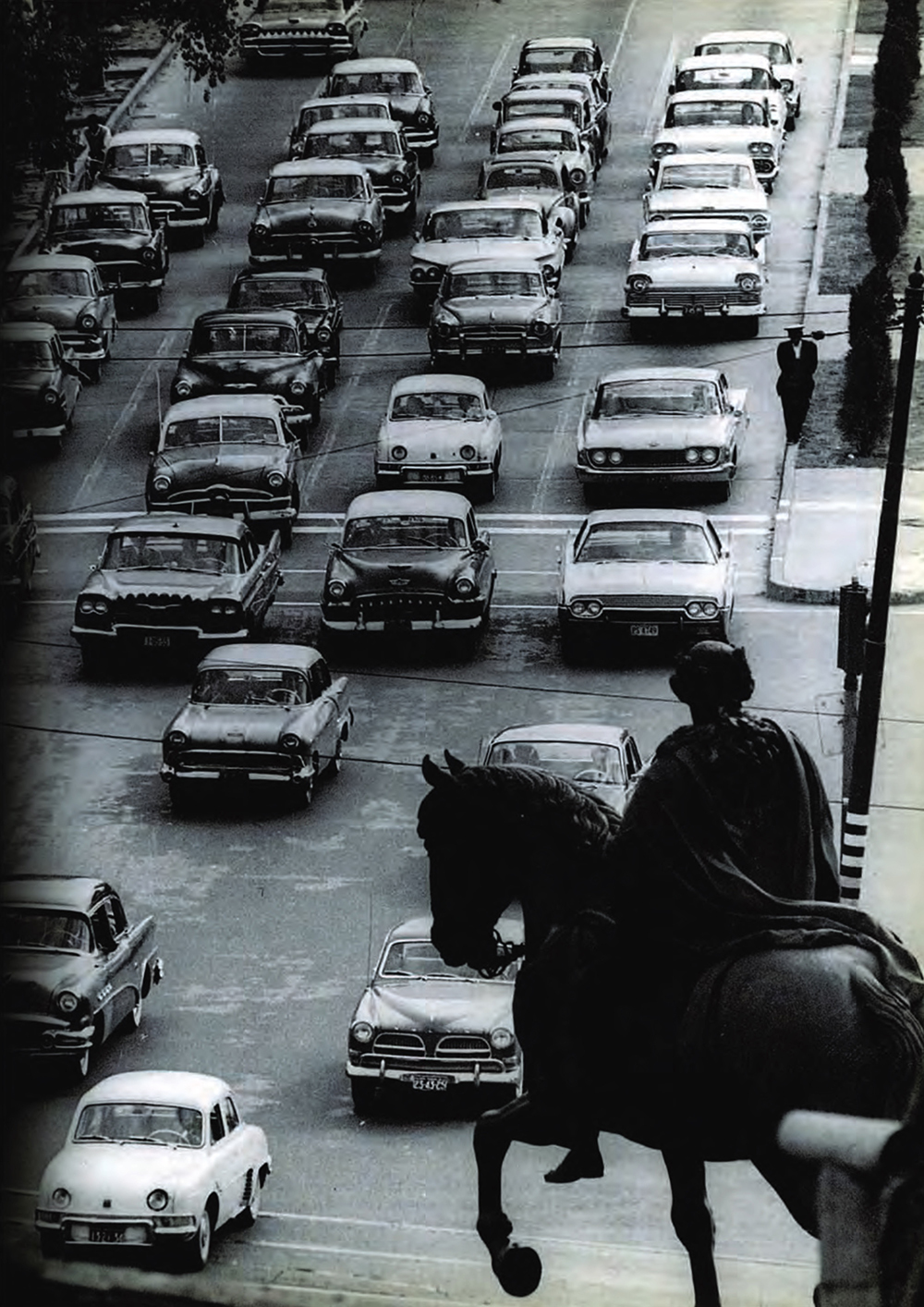

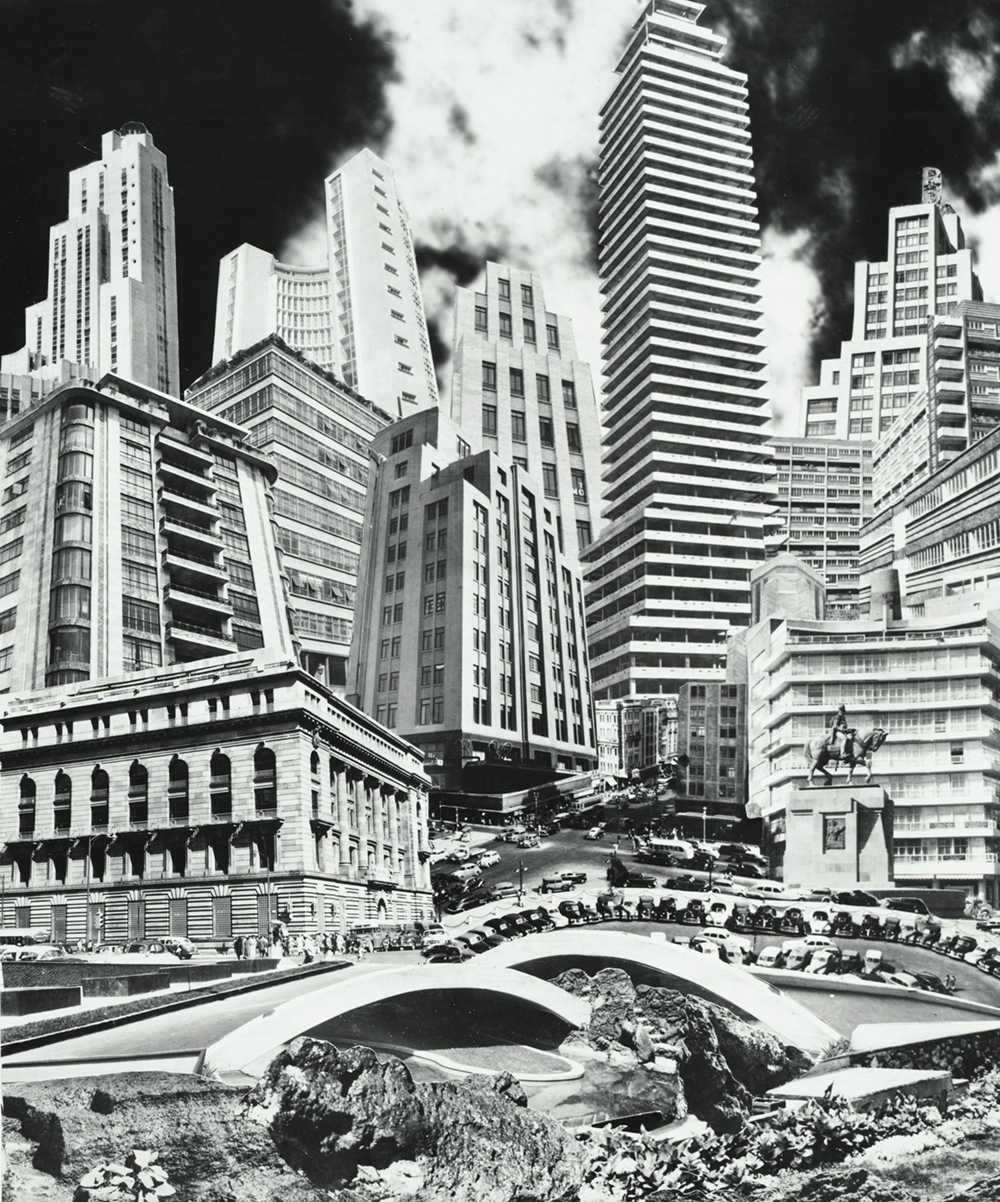

The automobile defined the distribution of urban space during the mid-twentieth century. By then, infrastructure for the exclusive use of automobiles was under construction, such as the Miguel Alemán Viaduct, the Inner Loop, and the Peripheral Ring. In her collage, Anarquía arquitectónica en la Ciudad de México (Architectural Anarchy in Mexico City), Lola Álvarez Bravo presented a critical vision of urban modernity with the automobile as one of its central elements. She highlighted the crowding of large buildings, avenues, bridges, overpasses, and parking lots.

In 1945, Alfredo Zalce reflected on the consequences of this great transformation in his painting Puente Nonoalco (Nonoalco Bridge), the first bridge built for automobiles in Mexico City. Located on what is now Insurgentes Avenue, it ensured the undisrupted flow of cars when passing over the railroad tracks at Buenavista and Nonoalco Avenue (today Ricardo Flores Magón), connecting the city to the Mexico-Laredo highway (today Insurgentes Norte). But Zalce did not paint the bridge as a monument of modernity but portrayed those who were left out of that route. As exclusive spaces for the use of cars, these infrastructures could favor an unequal use of the city. Who had access to the transport infrastructures that shaped the modern city?

Photographer Héctor García captured the vulnerabilities created by the streets in the mid-twentieth century. The footnote for his 1958 photograph entitled ¡Córrele! (Run!) said:

“Learning to survive… This girl learns from her grandfather one of the most difficult and dangerous things in the world: crossing a street in Mexico City. If the little one assimilates the lesson well, she will reach adulthood without being crushed by a bus. A thinker has already said it: In Mexico, pedestrians are a generation of survivors.”

The girl and her grandfather were probably two of the thousands of migrants from the countryside who arrived in Mexico City in the middle of the century. They did not own a car, but they lived in a city designed to privilege the circulation of motorists. We can assume that, before walking, they used one of the thousands of buses that connected the metropolitan area with the economic and political center of the capital city. However, buses, like trams, were not enough to transport over three million of residents by 1950.

By the middle decades of the century, there had been a transition towards a new dominant way of getting around in the city: motor vehicles. Old problems took on new forms: dependence on one form of transport to connect origins and destinations in the metropolis, crowding, traffic accidents, among others. With the standardization of space for the exclusive use of cars, discrimination, and vulnerabilities came to define the urban experience. Go to the Epilogue: Past Futures to reflect on the city and the mobilities that surround you.