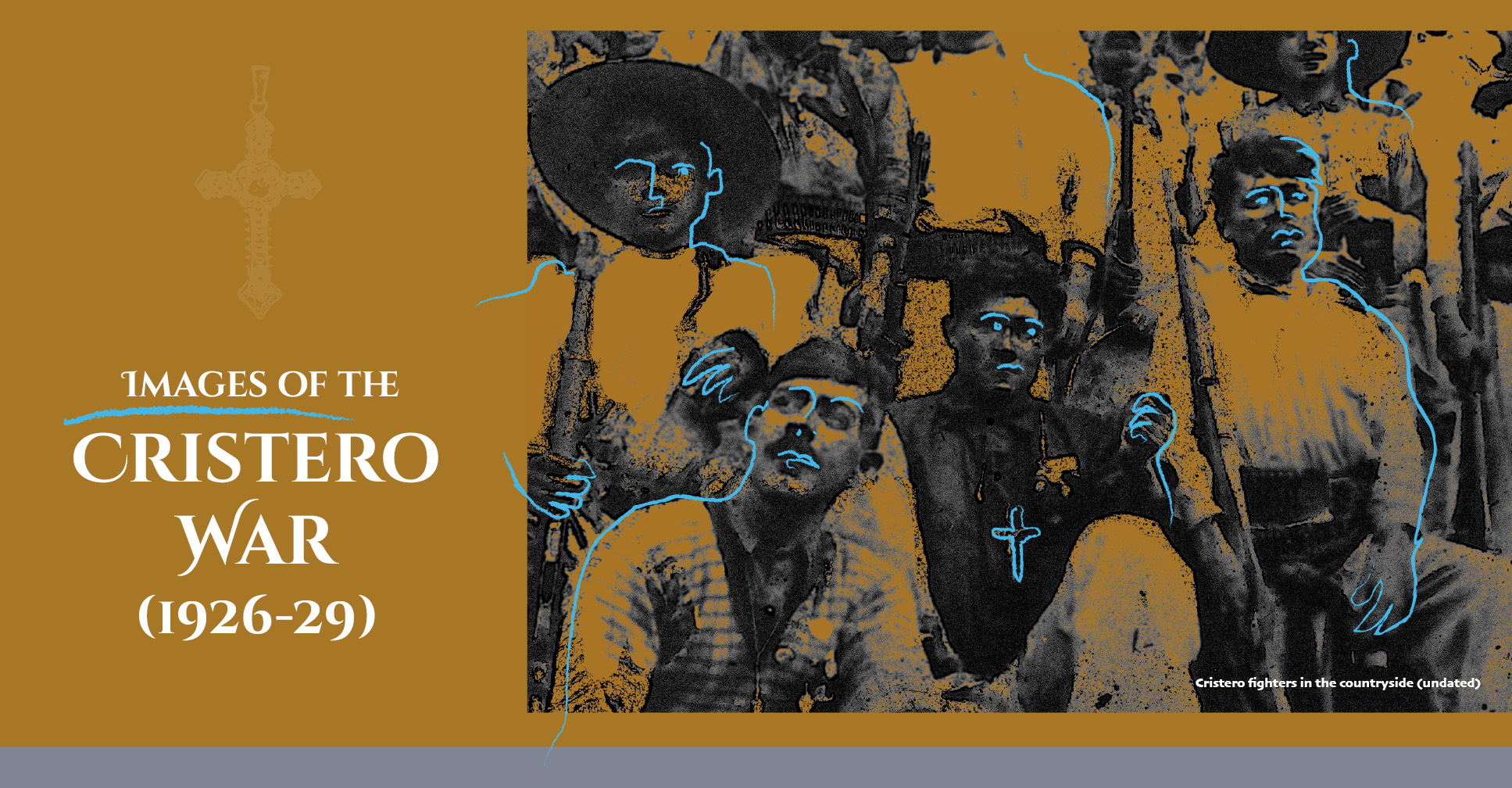

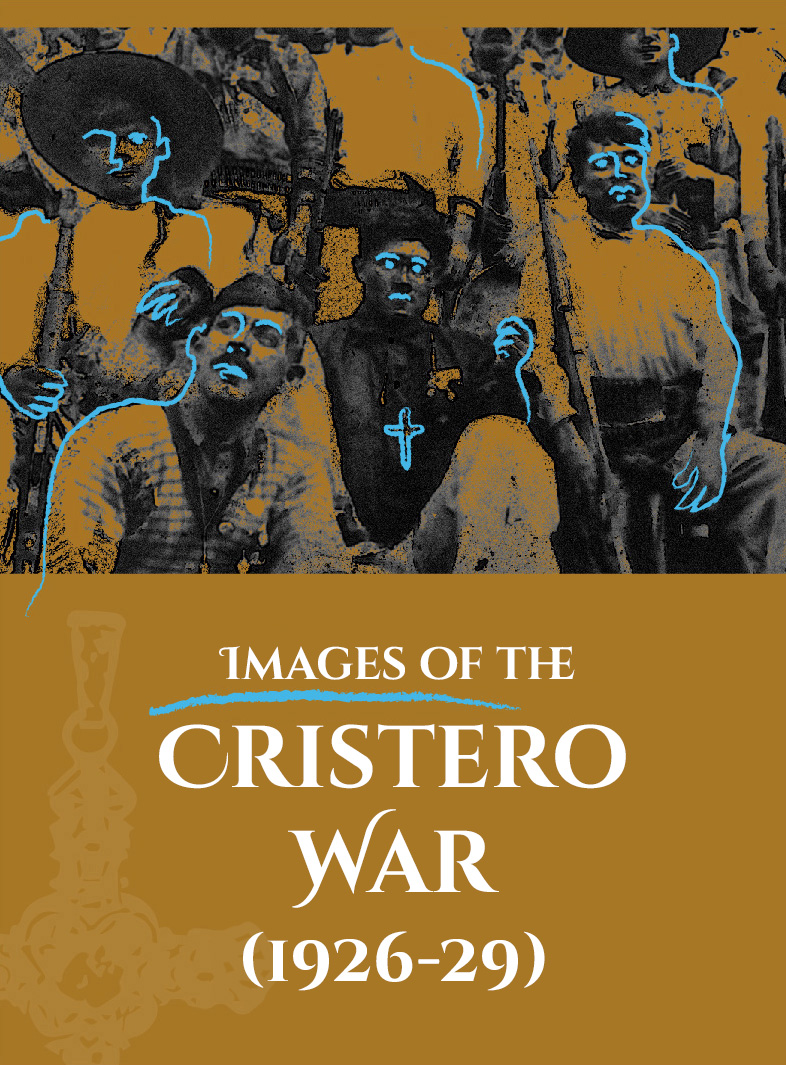

This photographic exhibition explores one of the most violent but perhaps lesser known episodes in Mexico’s recent history: The Cristero War (1926-1929). This conflict, also known as the “Cristiada”, erupted in 1926 when militant Catholics rose up against the anticlerical policies of the post-revolutionary government. The main trigger for the uprising was the decision of president Plutarco Elías Calles (1924-1928) to apply the anticlerical articles of the 1917 Constitution. The controversial “Calles Law”, which was enacted on the 14th of June 1926, established penal sanctions for any violation of the constitutional provisions relating to religion. Under the law, religious activities outside of church buildings, religious education in primary schools and political activity on the part of the clergy were all prohibited, among other measures. In protest against these restrictions, the Mexican Episcopate published a collective pastoral letter on the 25th of July 1926 announcing the suspension of all religious services.

When the National League for the Defence of Religious Liberty (LNDLR) declared a national revolt in response to the government’s “unjust and tyrannical” campaign of religious persecution, thousands of Catholics known as “Cristeros” took up arms under the slogan of “Long Live Christ the King!”. Between 1926 and 1929, the resulting Cristero War devastated the central-western region of Mexico, with the violence particularly concentrated in those states with a strong Catholic tradition such as Jalisco, Michoacán, Zacatecas, Guanajuato and Colima. The conflict came to an end in 1929 when the Mexican government and the Catholic hierarchy reached a peace agreement with mediation from the Vatican and the United States Ambassador. According to this pact, known as the arreglos, the Church agreed to recognise the authority of the government and to refrain from participating in political affairs. Although this agreement officially put an end to the war, the introduction of a secular and socialist model of education during the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940) triggered the so-called “Second Cristiada” (1934-38), a series of spontaneous and isolated uprisings which never developed into a national movement. The Cristero War triggered a wave of migration towards the United States and left a deep mark on political and religious life in Mexico. Memory of the conflict remains alive today in areas particularly affected by the conflict, especially the highland regions of Los Altos de Jalisco and the Bajío where numerous shrines and altars dedicated to Cristero martyrs are located. In political terms, the conflict deepened many Catholics’ distrust of the post-revolutionary state and paved the way for the formation of Catholic opposition movements and parties during the 1930s such as the National Synarchist Union (uns) and the National Action Party (pan). The Cristero War left a complex legacy in Mexican history and has given rise to contrasting interpretations and narratives. For some, the Cristero War was an uprising of religious “fanatics” spurred on by the clergy who refused to obey the law. For others, the conflict represented an epic crusade in defence of religious liberty. As we approach the centenary of the Cristero War in 2026, this photographic exhibition constructs a visual history of the conflict from different perspectives by bringing together over 40 images.

The suspension of public worship by the Mexican Episcopate in July 1929 transformed everyday religious life in a country where more than 90% of the population identified as Catholic. For the first time in 400 years, church bells fell silent and spaces of worship were abandoned in the absence of priests to provide religious services. However, Catholic worship continued underground: mass was delivered in front of makeshift altars in the countryside or in private homes which also provided an alternative space for religious education. It was not just a matter of relocating worship to clandestine spaces, but also of radically rethinking the administration of the sacraments. In the absence of priests or a hierarchical church structure, it fell to lay Catholics, sometimes including women, to deliver “white masses” and to celebrate weddings, baptisms and communions. These innovations demonstrate how, as historian Matthew Butler has noted, religious persecution triggered an ecclesiastic crisis for the Church in Mexico but it also opened up new opportunities for popular religious participation.

The Cristero cause was promoted and coordinated by various Catholic organisations. The most prominent of these was the National League for the Defence of Religious Liberty (lndlr), founded on the 14th March 1925 with representatives from various Mexican Catholic organisations such as the Knights of Columbus and the Union of Catholic Mexican Ladies, amongst others. The League initially promoted peaceful resistance against the Calles Law, supporting a petition calling for the law to be revoked and promoting a boycott to exert economic pressure on the government. When these methods failed, the League abandoned its non-violent campaign and declared a national uprising. Although the League had been founded in Mexico City (then Federal District), it soon expand its presence in central and western parts of the country and enjoyed a support network abroad thanks to organisations such as the Knights of Columbus in the United States and the Unión Internacional de Todos los Amigos (VITA-México) in Europe. Catholic women actively participated in the Cristero movement. For example, members of the Union of Catholic Mexican Ladies, an association founded in Mexico City in 1912, disseminated propaganda, promoted religious education and established clandestine eucharistic networks to sustain religious practise underground. Female Catholic activism also had a strong rural component during the armed conflict. Members of the Saint Joan of Arc Women's Brigades, formed in Guadalajara, Jalisco in June 1927, risked their lives to provide Cristero combatants with arms, ammunition and food supplies.

The armed conflict was concentrated in the Centre-West of the country, particularly in the states of Jalisco, Michoacán, Colima, Zacatecas and Guanajuato. The total death toll has been the subject of debate amongst historians: some state that it claimed between 70,000 and 90,000 lives while others estimate a higher figure. The majority of Cristeros and priests who died defending their faith during the Cristero war were considered martyrs and their cults spread rapidly through the dissemination of photographs and illustrated postcards which functioned both as evidence of state persecution and devotional images. One of the most memorialised martyrs of the Cristiada is the Jesuit priest Miguel Agustín Pro who was executed in November 1927 without trial with three other members of the League (his brother Humberto Pro, Luis Segura Vilchis and Juan Tirado Arias) after being accused of attempting to assassinate general Álvaro Obregón. As he faced the firing squad, Pro raised his arms in the form of a cross, creating one of the most iconic images of the armed conflict. Pro, whose final posture embodied peaceful resistance, was celebrated as a martyr by the Mexican ecclesiastical hierarchy and was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1986. More contentious was the case of José de León Toral, a member of the League and the Mexican Catholic Youth Associationacjm who assassinated Obregón in the La Bombilla restaurant in the San Ángel neighbourhood of Mexico City in July 1928. After a controversial public trial, Toral was executed on the 9th February 1929. Although the Catholic Church immediately distanced itself from the assassination, various Catholic groups venerated Toral as a martyr.

On the 21st of June 1929, three years after the outbreak of the Cristero War, an agreement was reached between the Mexican government and representatives of the Catholic Church which formally brought the armed conflict to an end. The principal negotiators were president Emilio Portes Gil (1928-1930), the secretary of the Mexican Episcopal Committee Pascual Díaz y Barreto, the Apostolic Delegate to Mexico Leopoldo Ruiz y Flores and the United States Ambassador Dwight D. Morrow, who participated as a mediator. Although the pact, known as the arreglos (the “arrangements”), enabled the resumption of public worship which had been suspended since 1926, the government refused to change the anticlerical laws which had triggered the uprising. The arreglos were perceived as a humiliating defeat by those Cristeros who were forced to lay down their arms and caused great confusion within the general Catholic population. This resentment and the introduction of educational reforms during the administration of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940), led to a rekindling of tension between conservative Catholics and the State during the subsequent decade which would ultimately culminate in the “Second Cristiada” (1934 – 1938).