The interest in science was one of the outstanding features of the 18th century, as these images from scientific journals of that time showing the attributes of the agave and the cochineal render proof.

Throughout the 17th century the American territories of the Spanish Empire had amassed an important political and economic autonomy in relation to the Crown. The arrival of the Bourbons to the Castilian throne at the start of the 18th century and the rise of Enlightenment ideas brought sociopolitical and governance transformations in addition to a new way of thinking centered on science and reason. Alongside the scientific ideas focused on categorizing and classifying, other ideas regarding human races developed. These ideas impacted the ways societies were understood, and with this came an ideology of racism that had its peak during the 19th century.

Upon their arrival to the throne of the Spanish Empire, the Bourbons, using the ideas of the Enlightenment, pushed a series of measures to take back political, economic and social control of the Crown. José de Galvez was in charge of carrying out said measures starting mid-18th century.

Bourbon reforms established mid-18th century looked to gain new control of the colonies. As part of said reforms, commerce was freed, new economic enterprises were created and the political power of the criollos dwindled causing dissatisfaction and disapproval. Social life also sought to have new coercive measures set in place. Among them, the Royal Pragmatic on marriages which prohibited the unions between persons of different “qualities” and economic standings. It also recommended using Fathers as granters of permission for marriages. Few requests for marriage in the New Spain followed the requirements of this regulation, but the ones that did followed it referred to the impediment of unions between Africans and Spaniards, or the other way around, as being unequal marriages. This also shows that, mid-18th century, social prejudices and the conception of “races” would grow and come to impact family and social relationships significantly.

Just like the natural world was cataloged and classified, the enlightened were obsessed with arranging social issues using “reason”. When these European ideas arrived to the New Spain, classifications started appearing in chronicles and essays. The subject of said classifications were marriages and mixed relationships among the different social groups of the New Spain; something that was rarely ruminated in daily life. In this context, and throughout the 18th century, casta or mestizaje (miscegenation) paintings started to appear in many countries of America, especially in Mexico. These paintings were created in order to show the diverse groups that formed the society of the New Spain. In them, there were depictions of family groups acting domestic and city life scenes as well as the occupations people used to have at that time. Couples with a son or daughter portrayed mestizaje and cultural diversity according to a complex classification system in which the terms hinted to skin color along with other elements like the person’s origins or colloquial nameing. However the terms depicted in these paintings were poorly correlated to the ones used at that time; most of them, like saltapatras, tente en el aire, albarazado, among others, were neither used in the documents of the New Spain nor in real life.

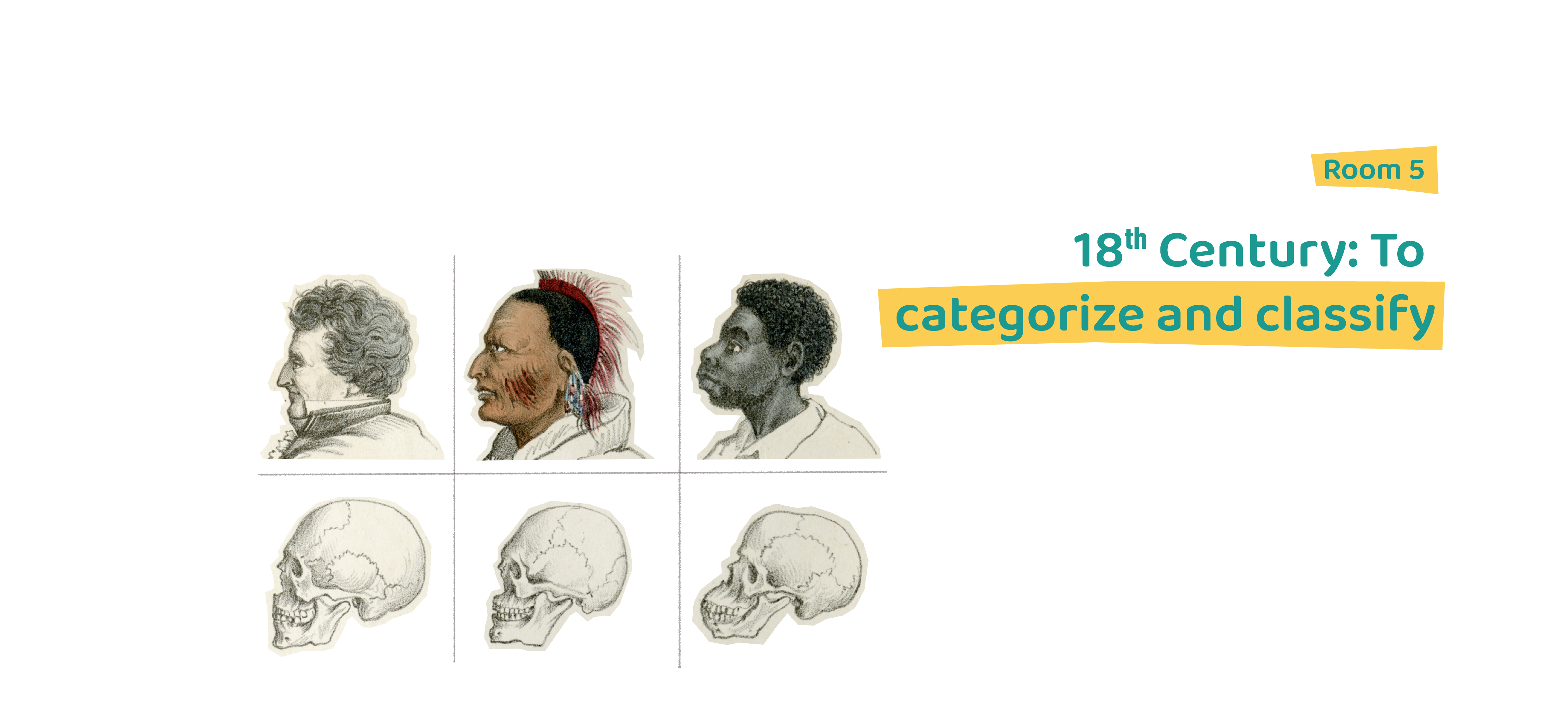

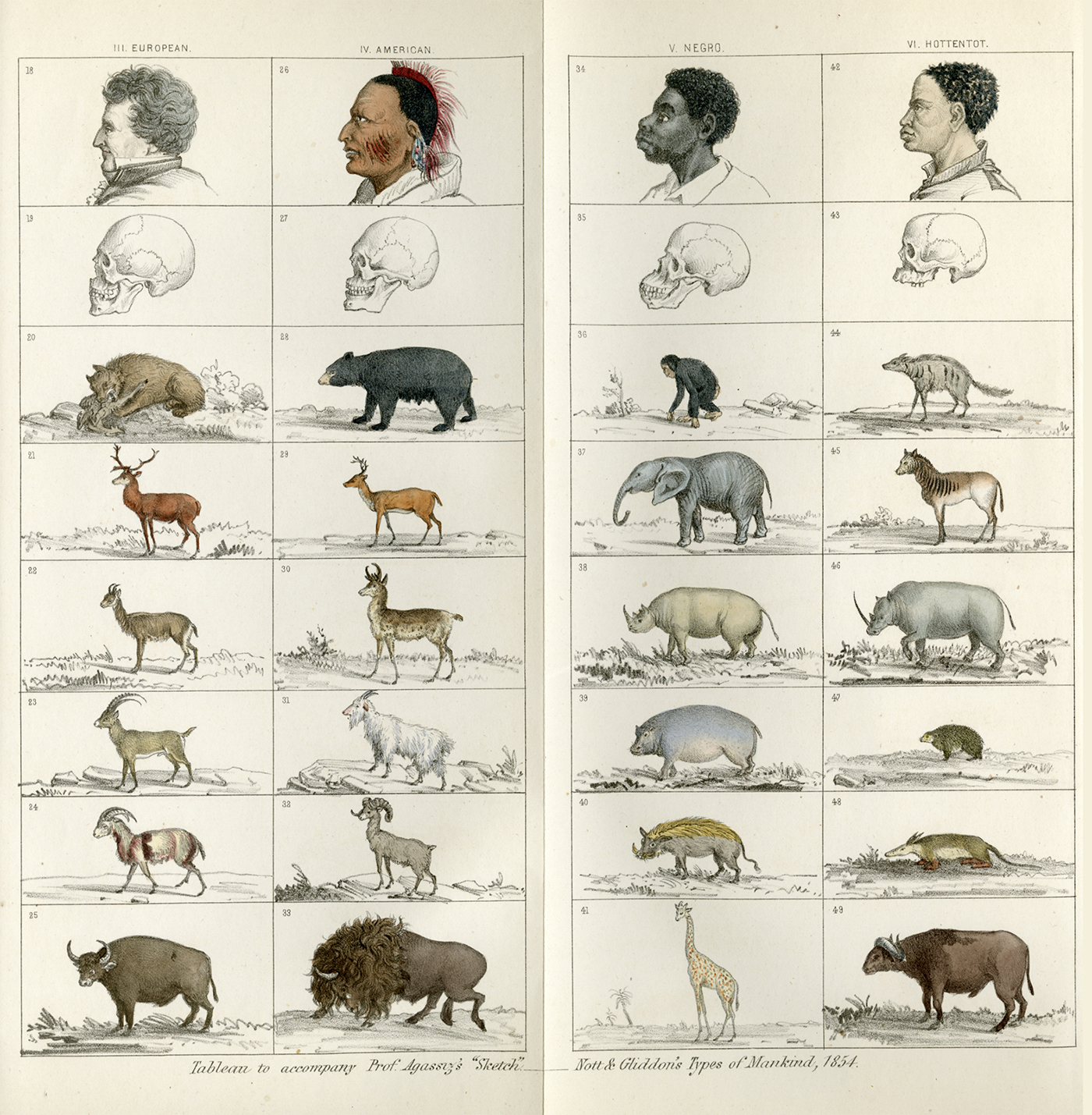

From Types of Mankind, graph by Nott and Gliddon: Center for the History of Medicine, Countway Library.

The ideas of “human races” emerged in the 18th century and promoted that certain human groups were inferior and others superior. This erroneous idea was popularized mostly to justify the growth seen in the African continent slave trade and the colonization happening in different parts of the world. Nowadays it is known that human beings are equals and belong to the same species.

Categorizing human beings in “races” was an invention of the 18th century. It sought to classify individuals and societies according to their physical characteristics, skin color, place of origin, customs, history and culture. This “pseudo scientific” effort had an economic and political purpose as to justify superiority among human beings by using reason and science as it means. This idea validated colonization, exploitation, slave trade and the subjugation of said colonies and new territories. One must remember that it was in the 18th century when the slave trade reached its peak in Brazil, the Caribbean and the United States. Nonetheless, other territories like Mexico acquired fewer slaves during this period, mainly because of the growth of a free workforce which made slavery unprofitable. Testimonial of the pollster for the Revillagigedo census in which he stresses the difficulties of classifying people: "It is not possible to have a census only for Spaniards, another one only for mestizos, another one for mulatos and another one for Indigenous people; because, of all the castas that live in the city, one can find people of all “qualities” in a same house, even in the same family in which the husband is of one kind, the woman another one and the children another one; for example, Spanish husband, Indigenous woman, mestizo children. Hence, for this same reason the specificities of the families weren’t noted; otherwise one would have to separate the Spaniards, mestizos and Indigenous people for each house in the multiple neighborhoods of the city."

(Joseph Antonio de la Via, ecclesiastical judge of the parish of Santiago de Queretaro in Mexico, 1777 census.)